Human Behaviour

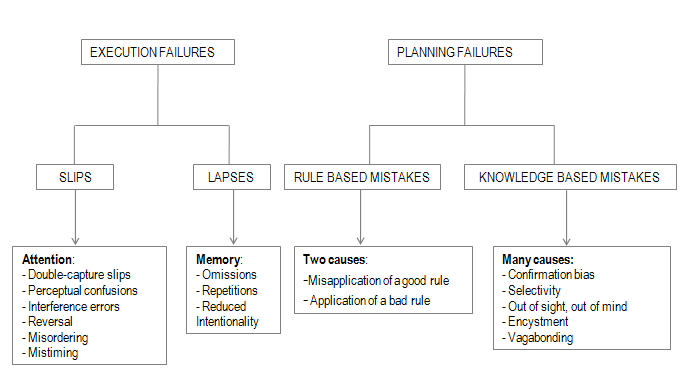

Content source: Content control:Errors are the result of actions that fail to generate the intended outcomes. They are categorized according to the cognitive processes involved towards the goal of the action and according to whether they are related to planning or execution of the activity.

Actions by human operators can fail to achieve their goal in two different ways: The actions can go as planned, but the plan can be inadequate, or the plan can be satisfactory, but the performance can still be deficient (Hollnagel, 1993).

Errors can be broadly distinguished in two categories:

Execution errors correspond to the Skill based level of Rasmussen’s levels of performance (Rasmussen 1986), while planning errors correspond to the Rule and Knowledge-based levels (see Figure 1)

In a familiar and anticipated situation people perform a skill-based behaviour. At this level, they can commit skill-based errors (slips or lapses). In the case of slips and lapses, the person’s intentions were correct, but the execution of the action was flawed - done incorrectly, or not done at all. This distinction, between being done incorrectly or not at all, is another important discriminator.

When the appropriate action is carried out incorrectly, the error is classified as a slip. When the action is simply omitted or not carried out, the error is termed a lapse. “Slips and lapses are errors which result from some failure in the execution and/or storage stage of an action sequence.” Reason refers to these errors as failures in the modality of action control: at this level, errors happen because we do not perform the appropriate attentional control over the action and therefore a wrong routine is activated.

A classic example is an aircraft’s crew that becomes so fixated on trouble-shooting a burned out warning light that they do not notice their fatal descent into the terrain. In contrast to attention failures (slips), memory failures (lapses) often appear as omitted items in a checklist, place losing, or forgotten intentions. Likewise, it is not difficult to imagine that when under stress during in-flight emergencies, critical steps in emergency procedures can be missed. However, even when not particularly stressed, individuals have forgotten to set the flaps on approach or lower the landing gear.

Once a situation is recognised as unfamiliar, performance shifts from a skill-based to a rule-based level. First of all, the human tries to solve the problem by relying on a set of memorised rules and can commit rule-based mistakes. These kinds of error depend on the application of a good rule (a rule that has been successfully used in the past) to a wrong situation, or on the application of a wrong rule.

In the case of planning failures (mistakes), the person did what he/she intended to do, but it did not work. The goal or plan was wrong. This type of error is referred to as a mistake.

When we recognise that the current situation does not fit with any rule stored, we shift to knowledge-based behaviour. At the knowledge-based behaviour level we can commit planning errors (Knowledge based mistakes). They basically concern the difficulty we have in gathering information on all the aspects of a situation, in analysing all the data and in deriving the right decision. Planning is based on limited information, it is carried out with limited time resources (and cognitive resources) and it can result in a failure.

Imagine the following situation. It’s 8:15 AM and you are driving to your office. The traffic is not moving at the usual pace and at some points it is not moving at all. You do not know what is happening: it might be an accident or something else but it will cause you to be late. In response, you devise an alternative plan: you decide to continue to work via a different route. You know the city, so it is easy for you. Unfortunately, road works make your brilliant plan a failure. The street you intended to use is blocked and you have to return to your usual route. It is possible that the road works on the alternate route were the cause of the traffic jam you encountered. Your plan was wrong. You did not have a good model of the city traffic.

The important point to understand is that error and performance are both merely the outcomes of behaviours and actions - these behaviours and actions are intrinsically the same, whether they result in a positive or a negative outcome. In fact, if the system performance criteria were not known, it would be difficult to observe human behaviour and say whether it was good or ‘in error’. A true model of error must therefore be able to account for performance and vice versa (HERA).

In raw frequencies, SB >> RB > KB

But if we look at opportunities for error, the order reverses: humans perform vastly more SB tasks than RB, and vastly more RB than KB so a given KB task is more likely to result in error than a given RB or SB task.

Effectiveness of self-detection of errors:

Including correction tells a different story:

Airbus