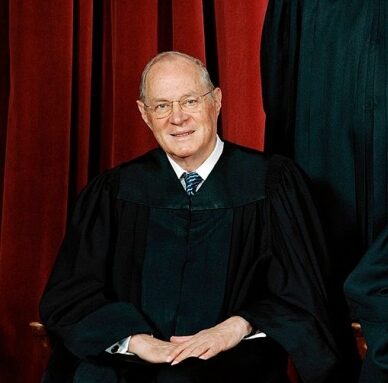

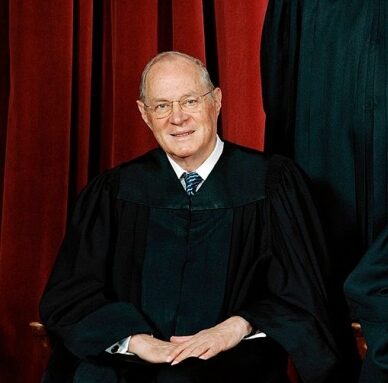

A law professor who tracked the justices' records in free speech cases from 1994 to 2002 found Justice Anthony Kennedy (pictured here in a 2009 photo) to be by the far the most speech-protective justice on the Supreme Court. Kennedy wrote the Court's majority opinion in the campaign finance decision of Citizens United v. FEC (2010), emphasizing that the corporate identity of a speaker does not justify content-based restrictions on speech. (Photo by Steve Petteway, Staff Photographer of the Supreme Court, public domain)

Since being confirmed to sit on the Supreme Court in 1988, Anthony McLeod Kennedy (1936 – ) has frequently been in the middle of his bitterly divided colleagues in First Amendment cases. Kennedy retired from the Court in July 2018.

Anthony Kennedy was born in Sacramento, California, and educated at Stanford University, London School of Economics, and Harvard Law School. He later entered private practice and taught at the McGeorge School of Law of the University of the Pacific.

In 1974, a seat opened on the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, and President Gerald R. Ford nominated Kennedy to the position. In April 1975, Kennedy was confirmed by the Senate, making him at age 38 the youngest federal appeals judge in the country when appointed to the bench.

In 1987 President Ronald Reagan nominated Kennedy to the Supreme Court to replace Justice Lewis F. Powell Jr., who was retiring. In early 1988, Kennedy was easily confirmed by the Senate, which had just dealt with the highly controversial and failed nominations of Judges Robert H. Bork and Douglas H. Ginsburg.

Throughout his time on the Rehnquist Court (Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist died in 2005), Kennedy and Justice Sandra Day O’Connor were the swing votes in First Amendment cases.

With O’Connor’s departure from the Court in 2006 and the appointments of Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. and Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr., both conservatives, Kennedy often became the sole justice in the middle — generally accommodating religion, but not always, and largely protecting speech, but leaving some space for government regulation.

Kennedy has sided with the liberals in key decisions on school prayer, political speech and obscenity. His overriding concern for liberty and his willingness to view the Constitution as a living document are important features of his First Amendment jurisprudence.

In free-exercise cases, Kennedy has joined with his fellow conservatives on the Court in adopting the neutrality test, a test put forth by the majority in Employment Division, Department of Human Resources of Oregon v. Smith (1990), which upheld the denial of unemployment benefits to two Native Americans who were fired from their jobs for ingesting peyote for religious purposes.

And yet Kennedy wrote the unanimous opinion in Church of the Lukumi Babalu Aye v. City of Hialeah (1993) that struck down a local ordinance prohibiting animal sacrifice, because the statute targeted the Santeria religion and therefore failed the neutrality test.

In the area of religious establishment, Kennedy has voted with his colleagues to accommodate religion, with a few notable exceptions. In cases on the religious use of public facilities and funds, Kennedy has always been an accommodationist.

In Rosenberger v. Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia (1995), for example, he wrote the majority opinion that held that student religious groups were entitled to the same state university student activity funds to produce a religious newspaper that student nonreligious groups received. His opinion in Rosenberger advanced the concept of avoiding viewpoint discrimination as a leading First Amendment principle.

Similarly, in cases on the government endorsement of religion, he has also been completely accommodationist, such as in Van Orden v. Perry (2005) and McCreary County v. American Civil Liberties Union (2005) in which he voted to allow Ten Commandment displays on public grounds regardless of the circumstances surrounding their placement.

In the area of aid to religious schools, Kennedy has also accommodated religion in every instance — such as school vouchers in Zelman v. Simmons-Harris (2002) — except one. In Board of Education of Kiryas Joel Village School District v. Grumet (1994), he invalidated a public school district that the state of New York had created specifically for a community of Hasidic Jews.

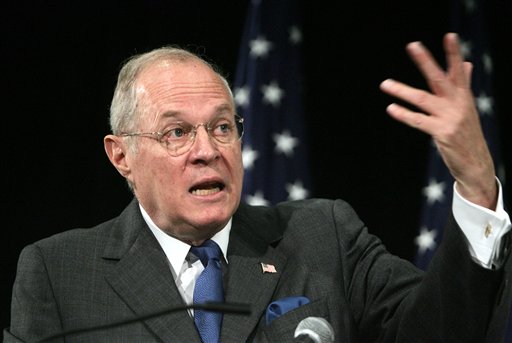

Supreme Court Justice Anthony M. Kennedy gestures during his speech after receiving the Franklin Award for his role in creating the Dialogue on Freedom program for high school students Monday, Sept. 19, 2005 in Washington during a National Conference on Citizenship luncheon. As a key swing vote on First Amendment issues, Kennedy generally accommodated religion, but not always, and largely protected speech. (AP Photo/Pablo Martinez Monsivais)

In school prayer cases, Kennedy generally has joined the liberals in separating church and state under the establishment clause.

In both Lee v. Weisman (1992) and Santa Fe Independent School District v. Doe (2000), he struck down invocations at public school functions. In this area, Kennedy is best known for introducing what became known as the “coercion” test.

However, Kennedy parted ways with the liberal wing of the Court in upholding town prayer in Town of Greece v. Galloway (2014). This decision confirmed Kennedy’s role as the key swing vote on the Roberts Court.

Kennedy has established a civil libertarian record in speech cases that has been generally skeptical of content-based restrictions on speech.

In Texas v. Johnson (1989), he provided the decisive vote that protected a protester’s right to burn the U.S. flag. And Kennedy has questioned campaign finance laws that seek to limit political contributions.

In his separate opinion in McConnell v. Federal Election Commission (2003), he explained that he viewed campaign donations as a mechanism of core political speech. He wrote the Court’s majority decision in Citizens United v. FEC (2010), emphasizing that the corporate identity of a speaker does not justify content-based restrictions on speech.

In extending his protectionist stance toward speech in public forums and the preservation of order, Kennedy voted in Hill v. Colorado (2000) to strike down restrictions on anti-abortion protesters. In both R.A.V. v. St. Paul (1992) and Virginia v. Black (2003), he voted to strike down cross-burning statutes as impermissibly content-based.

In obscenity cases involving children, Kennedy has voted to strike down federal laws that he found to be so vaguely written that they proscribed protected speech.

In Ashcroft v. Free Speech Coalition (2002), he delivered the majority opinion explaining that a federal child pornography statute was written so broadly as to impermissibly prohibit constitutionally protected speech such as scientific and artistic portrayals of children.

Supreme Court nominee Anthony Kennedy is sworn in before the Senate Judiciary Committee on Capitol Hill in Washington, Dec. 14, 1987. Kennedy was the key swing vote in many First Amendment cases, including Lee v. Weisman, in which he established the coercion test to determine whether the government has put pressure on an individual to support a religion. (AP Photo/John Duricka)

One major blight on Justice Kennedy’s free-speech record was his majority decision in Garcetti v. Ceballos (2006).

In that decision, Kennedy erected a new, categorical bar for public employees by holding that to sustain a free-speech retaliation claim, public employees must show that they spoke more as citizens rather than as employees pursuant to their official job duties.

In other speech cases, Kennedy has come close to being a free speech absolutist. In his concurring opinion in Republican Party of Minnesota v. White (2002), he ruled that the First Amendment flatly prohibited a content-based restriction on the political speech of judicial candidates.

Law professor Eugene Volokh, who tracked the justices’ record in free-speech cases from 1994 to 2002, found Kennedy to be by far the most speech-protective justice on the Supreme Court. Kennedy’s generally accommodationist stance on religious matters and yet speech protectiveness in the face of content-based restrictions reflect broader trends in the New Right political regime from which he was drawn.

This article was originally published in 2009. Artemus Ward is professor of political science faculty associate at the college of law at Northern Illinois University. Ward received his Ph.D. from the Maxwell School of Citizenship & Public Affairs at Syracuse University and served as a staffer on the House Judiciary Committee. He is an award-winning author of several books of the U.S. Supreme Court and his research and commentary have been featured in such outlets as the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Associated Press, NBC Nightly News, Fox News, and C-SPAN.